Why “diversifying and growing revenue from the audiences you build” is Table Stakes

Douglas K. Smith, Quentin Hope, Tim Griggs, Knight-Lenfest Newsroom Initiative,This is an excerpt from “Table Stakes: A Manual for Getting in the Game of News,” published Nov. 14, 2017. Read more excerpts here.

Innovate, test and develop as many ways as possible to gain revenue from the audiences you build, and the relationships you develop. Avoid the search for silver bullets – for the answer to the new business model. Do this by collaborating across all functions of your enterprise with a focus on innovating to grow consumer revenue and advertising as well as creating, testing and growing a range of new products, services and businesses of value to your target audiences and community.

Why this is Table Stakes

a) No business can survive without revenue and cash to pay for the work – an urgent challenge for metro news enterprises whose revenues and cash are declining

News organizations are not different from any enterprise in requiring cash to pay the bills. The cash coming in must equal or exceed the cash used to pay for (1) all expenses; (2) at least some investment in innovation; and, (3) any profit expectations of ownership. The same applies for nonprofit news organizations. When Philadelphia shifted to a nonprofit owner in January 2016, they eliminated profit expectations, but not the need for cash to cover expenses and innovation.

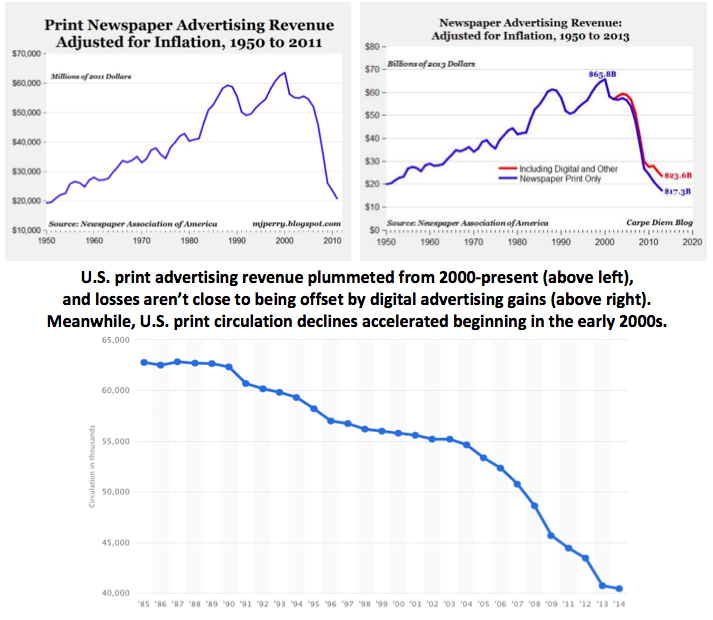

It has been a decade or more since the revenues and cash available to metros has been seriously declining.

b) The lucrative subscription-advertising-classifieds economics of print cannot be duplicated digitally because of important differences in the nature and structure of digital markets, costs and revenues

Print dollars, digital dimes, mobile pennies is – or should be – well known in your news enterprise. In the print era, subscriptions, advertising and classifieds combined to produce large, unassailable pools of revenues because metro, local and regional news enterprises benefitted from oligopolistic or monopolistic market structures. They along with some others were the only game in town. People and businesses wanting to stay current with news had few choices but to subscribe. Businesses that wanted to advertise to local audiences had few choices. Individuals seeking to sell or connect with others locally through classifieds had few choices.The lucrative subscription-advertising-classifieds economics of print cannot be duplicated digitally because of important differences in the nature and structure of digital markets, costs and revenues

None of this characterizes contemporary, digitally mediated markets. Potential subscribers have lots of choices – so many indeed that they have lost the habit of paying for content. Businesses have lots of choices for reaching and communicating with local audiences; and, with the rise of digital data and analytics, businesses can choose more precisely and pay less for the specific audiences they wish to reach. Individuals wishing to sell something to – or connect with –others in the community have lots of choices, many of which are free (e.g. Craig’s List).

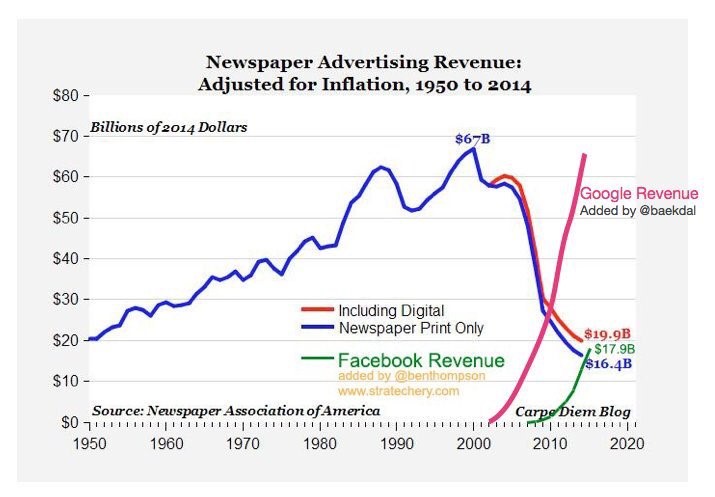

Digital revenues, then, will never be as robust or unassailable as print revenues. Ever.

That is, unless any enterprise establishes a monopoly or oligopoly market position – an enterprise such as Facebook in social. Google has similar market power in search. Monopoly and oligopoly are lucrative. No surprise, then, that Facebook and Google have so quickly dominated advertising revenues.

These shifts in market structure are well documented. What is less understood are the differences between print and digital in (1) the nature and structure of costs; and, (2) the relationship between cost and revenue.

Go back, say, to the late 90s and think about what folks in metro news enterprises knew at the beginning of each year regarding costs – namely, that it took a lot of money for printing plants, presses, and trucks as well as sizeable newsrooms filled with journalists and the circulation, distribution, marketing and sales staffs responsible for revenues.

The bulk of these costs were set. The challenge was generating enough subscription, advertising and classified revenues to pay for the set costs and generate returns to the owners – which, given strong market positions, was straightforward to do and do so profitably.

Costs were large, set and predictable. Revenues were large and predictable.

This changed with digital. Digital revenues for metros fighting to compete with so many other players are tiny, fluid and unpredictable. Yet, digital-related costs – e.g. for technology and tools – are not tiny. Though smaller than, say, printing plants, the costs for such things as content management systems are not trivial. They can be fluid and unpredictable though (for example, how often do you contemplate a new CMS with even better functions and features?)

Moreover, in the print era, costs were newspaper-related and revenues were newspaper-related. Profitability was simple to understand. Metros paid for costs that went into publishing the newspaper. Metros generated revenues from the newspaper. It was apples-to-apples: newspaper costs related to newspaper revenues.

Not so today. Consider the newsroom. In the web’s early days, some folks imagined that digital teams would repurpose print content. Had that worked, the revenues of digital could have offset the extra costs for those who digitally repurposed content. In other words, digital costs would relate to digital revenues in the same straightforward way as print costs related to print revenue: oranges-to-oranges (digital) to go along with apples-to-apples (print).

This didn’t work out as expected. As the industry’s experience and this entire report show, content for digital audiences cannot simply be repurposed from print. Instead, folks must work hard to create and publish content in ways that are tailored for digital audiences. The costs related to digital (oranges) and print (apples) are jumbled together. And revenues are as well (e.g. blended subscription offerings combining digital and print – apples and oranges).

“Is digital profitable?” has obsessed the industry only slightly less than “Can digital ever be profitable?” But, that is not a helpful question. It is a trap and a snare that diverts attention and effort away from the more critical, essential question: “How can we make our news enterprise profitable – or even financially and economically sustainable?”

Small, fluid and unpredictable digital revenues cannot cover large, set and predictable costs of print-oriented newsrooms. Digital economics cannot replicate print economics. The challenge today is how metro, local and regional news enterprises inexorably drawn into both digital and print can find as many sources of revenue as possible to pay for costs that are no longer simple to understand or manage. The only alternative to exploring and building multiple revenue sources is to cut costs – which eventually doesn’t work.

c) Geographically circumscribed markets prevent metros from using scale-based digital strategies

Even tiny per-use, per-click digital revenues can, if multiplied across zillions of folks, add up to attractive economics. Facebook, for example, had more than 1.9 billion users in mid-2017. In contrast, Philadelphia’s metros served a metropolitan area with just over 6 million people.

Six million sounds like a lot. But it’s miniscule compared with Facebook. Consider any sort of yield – batting average if you will. Say, a digital effort can successfully monetize 1 out of every 100 users – a yield of 1%. Do the math. Philadelphia, even if it reaches all 6 million people, has a yield of 60,000. At a 1% yield, Facebook succeeds 19 million times.

If the revenue generated is, say, 10 cents per success, Philadelphia reaps $6,000 while Facebook reaps $1.9 million.

Major metros such as Philadelphia, Miami, Minneapolis and Dallas have professional sports teams with fans spread across the nation. Might they pursue a scale strategy with those fans? Sure. But even if successful, they come up short in comparison with others such as ESPN that taps into unlimited digital scale because all fans of sports teams seek content at ESPN or Bleacher Report and so forth – enterprises for which geography is not a constraint.

Importantly, the benefits of social/mobile/web connectivity are available to any enterprise not geographically bound. For example, the award-winning single-topic enterprise Inside Climate News does not confront geographic barriers. Nor do BuzzFeed, Huffington Post, the Marshall Project, CNN, NBC, ABC, The New York Times, Washington Post, and a much longer list that grows every day.

There are exceptions for metros. Miami, for example, is the ‘capital of Latin America’; and, during Table Stakes, Miami experimented with ways to take advantage of this digital scale and reach.

Importantly as described in Table Stake #6, news enterprises also can find ways to partner with one another to reach beyond geographic boundaries. To illustrate, imagine a handful of metros partnered on a product or service responsive to audience needs common to them – for example, say, an app that helped folks find housing. Zillow, of course, is a competitor. But, if metros partner together, they could reasonably aspire to digital reach and scale strategies that none of them alone could make happen.

Such exceptions aside, metro, local and regional publishers have no choice but to find as many ways as possible to generate revenues locally through strategies not dependent on large digital reach and scale.

d) Cost reductions and/or industry consolidation do not eliminate the need for revenues and cash

Revenues must exceed costs. This is true even for nonprofits: unless the donations, income on endowments, major gifts along with any commercial revenues exceed the costs, the nonprofit will go out of business.

One way to ensure revenues exceed costs is to cut costs. But, you cannot cut costs to zero. At some point, costs are rock bottom and the only choice remaining is to generate revenues.

This same inexorable logic applies to industry consolidation. As Penny Abernathy reports in “The Rise of a New Media Baron and the Emerging Threat of News Deserts,” private equity, hedge funds, and other corporations buying up news organizations have a standard playbook of aggressive cost cutting combined with financial restructuring. For Wall Street investors, this promises attractive gains. In practice, it also can lead to what Abernathy calls ‘news deserts’: formerly robust newsrooms hollowed out and bereft of revenues needed to do their work.

Low-cost strategies, then, have limits. There is, though, another crucial point. Knight and Temple initiated the Table Stakes effort out of concern for the role local journalism plays in preserving and advancing democracy. That purpose demands strategies grounded in creating value for customers. Yes, value within responsible cost structures. Value-based approaches, though, require revenues and cash linked to value as opposed to relentless cost cutting.

e) The profound disruption of the early 21st century provides opportunities for metros to reinvent the value they create and reap – opportunities to generate revenues in ways that include but go beyond subscriptions and advertising

Solving the revenue side is the challenge facing metro, local and regional news enterprises in search of economic and financial sustainability. A part of the solution lies in putting audiences first – particularly local audiences – in search of as many ways as possible to attract, engage, and retain audiences who generate revenues through paying for content and/or advertising.

Digital subscriptions and advertising, though, will not suffice to cover print era costs – including the size of print era newsrooms – for metros, locals and regionals confined to geographic markets that preclude digital reach and scale strategies.

That’s the bad news. The good news arises from the many opportunities emerging from the ways metro, local and regional publishers might respond to the consequences of how digital disruption has combined with widespread industrial consolidation, globalization, deregulation and other powerful forces to reshape – even blow apart – local economies and communities and how folks approach the problems and challenges of their lives locally.

Where do I find a job? How do I make do on a fixed income? Should we send our kids to charter schools? What are my options to get home at rush hour today? How can I help my aging parents understand Medicare options? What are my rights and my landlord’s obligations to remove lead paint? What is the quality of our local water? I’m new in town and love jazz – where are the best places? My boss runs the local ACE hardware outlet and has asked me to come up with a social/mobile marketing plan. We’re part of a global bank whose brand has been hit hard by a settlement for mistreating consumers – how can we overcome the negativity locally? Our hospital has to figure out how to work with folks locally to reduce the adverse effects of such social determinants of health as food deserts, poor transportation options, and little time for exercise in our schools.

These are but some of the local problems metros might help solve for people and organizations. For people, problems fall in five categories (1) help me/us be informed citizens in the place I/we live; (2) help me/us solve the necessities of my/our lives; (3) help me/us enhance the quality of my/our lives beyond necessities; (4) help me/us work with others to make the places we live together better; and, (5) help me/us have the confidence that you are holding powerful people and institutions accountable.

Meanwhile, enterprises from all three sectors (private, nonprofit and government) confront local problems across a broad range from how best to reach, market, sell and serve customers all the way to figuring out how to fulfill obligations to local communities (e.g. hospitals, schools, local government agencies and so forth).

Note in particular a major problem arising from the disruption of local communities and economies: the deep need people have to connect with one another, especially in real life.

The explosive growth of social media responds to the hunger for relationships – for connectedness with other people. Yet, as important as social media interactions are, they still happen virtually and not in real life. For example, Philly’s chosen vision to be ‘the local leader in news, information and connectedness” embraces how best to connect folks in Philadelphia to one another through shared information and news (traditional), virtual interactions (social media) and in real life.

Metros that figure out how to solve local problems confronting people and enterprises – including the need for connectedness – create value. Creating value, though, is a necessary but not sufficient condition for success. Metros, locals and regionals also must figure out how to reap value from the value created. And that means monetization.

Monetization must include more than the two standard solutions of legacy mindsets: consumers who subscribe to our news offerings and/or advertisers who pay to reach customers. Dallas, for example, is part of Belo’s intentionally constructed ecosystem aimed at generating revenue from audience development, content marketing, events, digital optimization and other services. Miami’s “Food Inc” experimented with ticket sales to attend celebrity chef prepared meals. Minneapolis sold commemorative editions when Prince died. Philadelphia got cash from local foundations to support a “Next Mayor Project.” The New York Times doubled down on revenues from affiliate links with the purchase of Wirecutter.

These illustrate a new mindset – one that conscientiously avoids limiting revenue types to subscriptions and advertising – and instead considers as long and creative a list as possible of other approaches: product or service sales, commissions, membership, joint ventures, referral fees, ticket sales, licensing, business-to-business services, contributions, major gifts, endowments, software and/or technology sales/licensing, fundraising and more. The question is: What are the many ways we the metro, local or regional news enterprise can find to generate the cash that we need?