Three ways to close talent and skill gaps in your newsroom

Douglas K. Smith, Quentin Hope, Tim Griggs, Knight-Lenfest Newsroom Initiative,This is an excerpt from “Table Stakes: A Manual for Getting in the Game of News,” published Nov. 14, 2017. Read more excerpts here.

Close the gaps

There are three pathways to close talent and skill gaps in your newsroom:

- Holding already employed folks accountable – as individuals and teams – for learning, practicing and excelling at performance results related to the required skills/talents

- Identifying, attracting, hiring, and onboarding new folks – then holding them accountable in the same ways you do already employed folks

- Partnering and/or using independent contractors – and again holding all accountable for results

Imagine, then, headline writing. It is table stakes for reporters to get good at the headlines that drive traffic and engagement because:

- Content must be findable, shareable and explore-able. Headlines determine find-ability (search) and share-ability (social).

- Internet speed requires reporters do this themselves. When others write headlines for reporters, it takes two steps instead of one. It’s slower. And slowness means missed traffic and engagement.

- Audience-first strategy demands adopting and responding to the audience’s perspective. The first thing audiences see are headlines. When reporters pitch headlines, they get good at succinctly describing the story in terms of why the audience cares. If someone else is doing this for the reporter, then that reporter does not understand the connection between the story and the audience.

This is a skill and attitude shift for print reporters because (1) headlines that work in print differ from headlines that work in digital; (2) print reporters were not always responsible for headlines; and, (3) print headlines came as the last step when today they come first.

Consider the ‘headline rodeo’ at the Dallas Morning News. Each morning the folks in Dallas gather to decide which stories to emphasize through: (1) discussing a series of proposed headlines crafted to convey the essence of proposed stories; (2) workshopping those headlines to make them better; and, (3) reviewing/debriefing how previous headlines actually performed.

In Dallas, it is table stakes for reporters to be good not only at headlines that are findable/searchable and shareable but also headlines that distill the essence of a story from an audience-first perspective. Philadelphia also has a version of a headline rodeo. And they expect reporters to grasp an additional nuance: the difference that sometimes exists between web headlines (search engine optimization) versus promotional headlines that are not related to search algorithms. As Erica Palin of Philly pointed out in a note to her newsroom colleagues:

- “Web headline = the headline that appears on your story on Philly.com and will show up on Facebook and Twitter when someone shares your story. This is the headline that Google scrapes and looks at for keywords and SEO. Once this headline is live on Philly.com, we shouldn’t change it (unless there’s a spelling or fact error). Reporters should write this — with guidance and help from assigning editors/copy editors.

- Promo headline = the headline that appears on the homepage and section fronts. Sometimes this is the same as the web headline, but not always. This is written by producers and can change throughout the day. Google does not read this headline for SEO purposes.”

In the days of print, neither reporters nor others worried about such distinctions.

With headline-related skills and attitudes in mind, consider reporter X in your newsroom. Here are the key steps you must take:

- Does Reporter X already know how to use headlines to drive traffic and engagement as well as pitch stories?

- If yes, great! Encourage X to keep getting better – and seriously consider asking X to work with others in or beyond X’s team because peer-to-peer help is powerful.

- If no, X has a skill gap to close.

- Is Reporter X trying?

- If yes, great! Just make sure X commits to specific traffic and engagement performance results that benefit from X’s efforts

- If not, what actions might increase the odds that Reporter X is motivated to try?

- If Reporter X has a gap and is trying, how can you use Reporter X’s commitment to headline performance results as a condition and context for providing help? For example, how might you make X’s commitment to specific results the ‘price’ X pays for the opportunity to attend training and workshops, or get help from a digital specialist or peer?

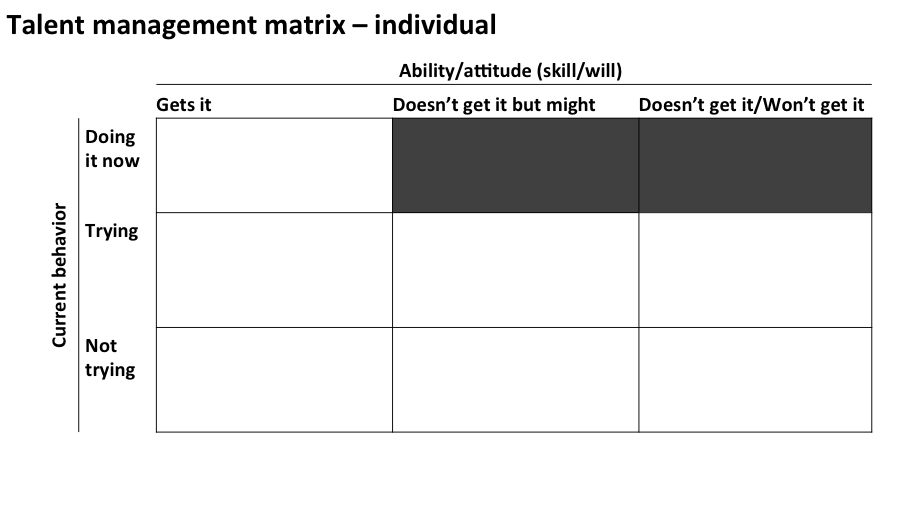

Such questions determine where – in this illustration with regard to headline skills – Reporter X is positioned in a talent management matrix:

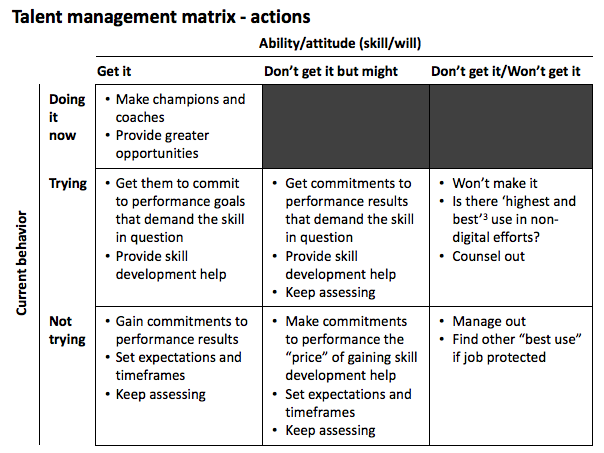

Consider any “Reporter X” in your newsroom. Think of ‘it’ (e.g. ‘gets it’) as headline writing. Where would you place X on this matrix? Now use this version of the talent management matrix to identify actions you must take:

Consider any “Reporter X” in your newsroom. Think of ‘it’ (e.g. ‘gets it’) as headline writing. Where would you place X on this matrix? Now use this version of the talent management matrix to identify actions you must take:

The essential step is getting Reporter X to commit to performance results that depend on X getting better at headlines – as opposed, say, to attending headline training.

The folks in Miami demanded that all reporters increase traffic by 7.5% – and then increased the odds of success by providing skills training to help reporters succeed. So did Dallas (though they used 10% as well as performance increases in a specially tailored engagement index).

Who is responsible for managing talent – for managing and guiding the transition of folks who must learn new skills such as headline writing? The answer:

- First and foremost, each individual is responsible for her/his own performance and change. No one can do this for them. If Reporter X wishes to get good at headlines, then Reporter X must take responsibility for doing so.

- Second, teams must take responsibility for the skills of individual team members. Minneapolis’ newsroom has roughly 250 folks. Senior newsroom leaders cannot keep tabs on so many individuals. Teams need to do that.

- Senior leaders must keep tabs on the teams – and use the talent management matrix to guide them. Senior leaders might pay attention to particular individuals such as team leaders and folks who can influence overall performance results and/or change momentum either positively or negatively.

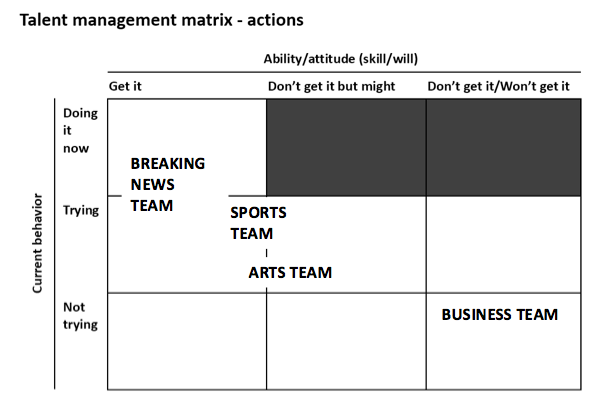

Teams should use the talent management matrix to position, then migrate, individuals to the upper left box. Senior leaders should use the matrix to position, and then migrate teams to the upper left box. Here’s an illustration for the team view of the matrix:

The ‘it’ in the matrix varies depending on jobs, roles, skills, attitudes and working relationships. For example, in Philadelphia, the ‘it’ included writing web headlines, adding links to a story on the website, adding photos to a story on the website, tweeting, posting on Facebook, verifying the authenticity of a source on social media, identifying when a topic is trending on social media and worthy of coverage, making a correction to a story on the website, using tools like Slack to communicate with other staffers, and moderating comments on the website.

In addition to using the talent matrix to guide already employed folks, you can also use it to consider additional options for closing gaps: hiring new folks and/or partnering with others, including independent contractors.

There’s good news in this. Consider the skill differences among digital natives (people who have grown up from childhood with digital technology), digital emigrants (people who have embraced digital technology as adults), and digital nevers (people who don’t get it and won’t get it). Today, there are millions more digital natives and digital emigrants than, say, in 2002 or 2005. Your newsroom has more opportunity than ever before to identify, attract, hire and onboard folks with key skills. Even in the face of tight budgets, Philadelphia, Minneapolis, Miami and Dallas took advantage of the growing labor supply of digital natives and digital emigrants to fill digital producer, audience developer, coder/developer and platform owner jobs and roles.

They also learned that what happens after such folks are hired matters a lot. In particular, metro newsrooms must overcome:

- Digital divide: In the autumn of 2015 (just at the beginning of the Table Stakes effort), folks with digital skills in all four newsrooms were frustrated about isolation and being “after thoughts.” These concerns arose from print-centric culture and practices. It was commonplace for a significant story to be all but fully complete before the digitally skilled folks were asked to get involved. Instead, folks lamented that stories would be done, then “thrown over the wall” with the request to “make it work on digital.”

- Print-driven meetings and choices: Prior to the Table Stakes efforts, the daily meeting flows were print-focused and habits such as ‘hold that story for Sunday’ marginalized folks with digital skills.

- Do it for them (not with them): Digital specialists spent nearly all their time doing digital work for others instead of with Consequently, skills were not getting acquired or practiced by most folks in the newsroom.

- Boredom and lost opportunity: People with significant skills – whether audience developers or coders or others – were not being challenged enough. They joined their metros with a deep sense of mission and wanted to make a difference. But, too often, senior leaders and others were not asking them to make much difference at all. Few were specifically asking digital experts to lead and/or contribute to the major transformative efforts critical to getting metro newsrooms into the 21st century.