How The Durango Herald partnered to use a solutions-based approach to produce a youth suicide project

Claudia Laws, David Buck, Mary Shinn, Sarah Flower, The Durango Herald,This is a series on Better News to a) showcase innovative/experimental ideas that emerge from the Knight-Lenfest Newsroom Initiative and b) to share replicable tactics that benefit the news industry as a whole. This “win” comes from Assistant City Editor David Buck, Special Topics Reporter Mary Shinn and Audience Development Manager Claudia Laws of The Durango Herald in Colorado and freelance audio journalist Sarah Flower. The Durango Herald took part in the Poynter Institute’s Local News Innovation Program in 2017-18.

API and Poynter teamed up to take a deeper look at The Durango Herald’s experience with transforming itself. Here, you can read about how the news organization applied specific lessons from Table Stakes for this project, and over at Poynter, you can read how the newsroom broke out of its silos to cover an important topic.

Question: What problem were you trying to solve, and why was solving the problem strategically important for your organization?

Answer: Suicide is a significant issue in our community, and Native American and LGBTQ youths are particularly at risk.

We’ve had out-of-town journalists “parachute” in and use the county as a vehicle to tell a larger story about the problem of suicide across the Mountain West. The name of the river running through town, the Animas River, is often erroneously translated to mean “River of Lost Souls.” That makes it easy for reporters to romanticize when they are writing about suicide.

Meanwhile, The Herald’s longtime approach to covering suicide has been to report the deaths of individuals as they happen. We adopted this approach decades ago at the request of our owners to shed light on the issue and to humanize those residents who died. We faced some criticism for our practice, especially as more young people started to die by suicide.

But moving forward, we wanted to be a catalyst for community conversations by focusing on solutions that would help teens and members of high-risk groups.

For this project, one part of our target audience was simply anyone in our county who has been affected by suicide. And, sadly, that’s nearly everyone. So, as an example of being solutions-oriented, we included a story about the importance of seeking grief care.

By focusing on solutions, we helped readers understand the issue — and see that the newsroom cares about the community. The problem is daunting, but we gave readers hope that suicides can be prevented.

Q: How is this approach related to Table Stakes (e.g. one of the7 Table Stakes and/or an outgrowth of the Knight-Lenfest initiative, etc.)?

A: This approach is directly related to Table Stake No. 1: Serve targeted audiences with targeted content; and Table Stake No. 6: Partner to expand your capacity and capabilities at lower and more flexible cost.

Q: How did you go about solving the problem?

A: Before launching the project, Amy Maestas, the Herald’s executive editor at the time, and Claudia Laws, the audience development manager, met with groups working on teen mental health issues. This included folks from school districts and health clinics, as well as nonprofits focused on suicide prevention.

The group identified a major problem: When residents searched for information about suicide in Durango, instead of finding clinics and help lines, they were more likely to find stories about deaths by suicide in town.

So the newsroom built DurangoCares.com, a website that would be separate from our news site but benefit from our SEO ranking. DurangoCares.com does not contain news content; it is the only site in the community that lists all the mental health and suicide-prevention resources available to residents.

Local mental health experts had always wanted such a website — and the site really benefited from the newsroom’s skills, including research and writing, managing websites and using SEO.

Photos for the solutions-based suicide project hang on the wall in The Durango Herald’s newsroom main meeting room.

Next, with the help of $5,000 grant from the Solutions Journalism Network, we hired a freelance audio journalist, Sarah Flower, to work with reporter Mary Shinn to expand our traditional audience. Sarah not only produced the 10 audio stories for the project, but she also helped report and research almost all the stories. This helped expand what a single reporter could have done alone.

Because of Sarah’s connections, the audio stories aired on three local radio stations, including one serving the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, expanding our coverage to a population we don’t typically reach.

The series, which included 14 written and 10 audio stories, examined youth suicide prevention programs and initiatives that promote social connections. This is important because when young people have relationships with caring adults and peers, those connections can lower their risk of suicide.

We also highlighted suicide prevention programs in schools, health care settings and clubs. We looked for programs that had shown measurable success in other communities and had been implemented locally.

Certainly, the nonprofit mental health provider that serves Medicaid patients in the community has many shortcomings. But we decided to save some of the material about the shortcomings for a different story and focus on the nonprofit’s implementation of the Zero Suicide model. That model has been successful in Detroit and is being adopted across the country by health care providers.

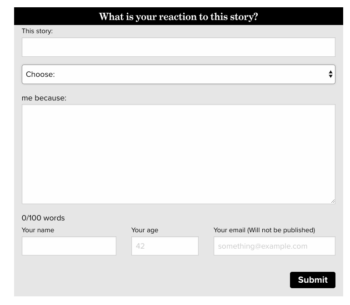

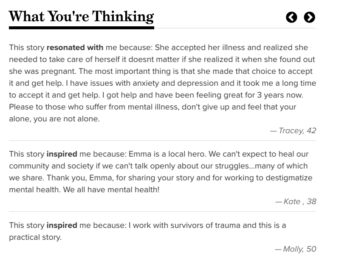

We adopted the approach to guided commenting that The Seattle Times has used as a means to elevate the conversation around the series, help readers to think more about their responses and to limit trolls. We did not post comments without prior review. We encouraged poignant and thoughtful comments from community members outside our “frequent flyers.”

After the series was published, the staff organized a panel discussion to explain to the community how and why the series was reported. The panel, which was held as part of a twice-a-month storytelling series (you can read more about this storytelling project here), allowed readers to ask tough questions and get honest answers.

Q: What worked?

A: Pairing an audio journalist with a reporter worked well. Through their complementary storytelling techniques, Mary and Sarah created a complete multimedia package.

The audio stories conveyed the emotions of those who have experienced loss by suicide in way that is impossible with text. The written stories provided expanded context and statistics. Mary and Sarah also received help from the staff photographer, who was given time to take emotional or illustrative photos for each piece, including most of the audio stories.

The reporting process helped rebuild trust between the newspaper and other community organizations. For example, the newspaper had a tense relationship with the main organization serving local LGBTQ youths that stemmed from past misunderstandings. But after our new series was published, these folks have participated in follow-up stories about other topics.

In addition, KSUT, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe’s radio station, picked up the audio stories in the series. Suicide is a significant problem within the tribe. But culturally, Southern Utes do not discuss death, as they believe it can bring death to those who discuss it. So for the tribe to air the series was a marked success.

The guided commenting on the website was also a win for us. We had fewer comments than on a breaking news story, but more than we had expected, ending up with around 65 comments.

Q: What didn’t work?

A: We initially thought that we were limiting our topic by focusing on youth suicide. But as we reported the stories, we realized that the topic was actually too broad. We ended up with great content, but we do wish we had limited the scope more at the onset (for example, looking at youth suicide prevention through a health lens or an education lens).

Our deadlines were too tight. Pretty much everything took longer than we thought it would. Thankfully, we had built in time for the project to be completed earlier than required for the grant, so we were able to give the reporters additional time.

Q: What happened that you didn’t expect?

A: The solutions framework resulted in more community assistance than we typically receive. For example, the police department gave us some data at minimal charge as the department’s data analyst was also interested in the data we requested and felt that our project would also inform the department’s work.

We also didn’t plan to produce 24 stories total. The initial proposal was for three. But given the high interest in the issue, we decided to run more content than perhaps we otherwise would have.

David Buck, the project’s editor, suggested that instead of six days in a row, we run stories in print twice a week for three weeks. That decision made the series easier for readers to digest.

Q: What would you do differently now? What did you learn?

A: If we had it all to do over again, we would start with a much more defined question. In this case, the question was, “What should we do to solve youth suicide?” We were pleased with our coverage, but a more focused project could have been completed with less staff time.

Q: What advice would you give to others who try to do this?

A: Plan for extra time. The solutions framework and its detail-oriented approach require more time than the average enterprise story.

Someone once told us that solutions journalism is more of a guide dog service than watchdog reporting. We found that to be true. The solutions lens inspired the reporters and editors involved with this project, as well as the entire newsroom.

It was also key to have staff working on different levels. Our executive editor was the visionary for the project, but David was the one who worked with the team to apply the solutions framework each and every day. His solutions-oriented questions took our reporting to places we otherwise might not have gone, in some cases allowing us to narrow our scope. We decided to focus on solutions that were working, here or elsewhere, instead of diving deep into the problems of our main local nonprofit mental health provider.

Q: Anything else you want to share about this initiative?

A: The endeavor was incredibly ambitious for us. We are a small team: One reporter is 25 percent of our reporting staff. The time devoted to this project was incredible. But it’s OK to be ambitious. It’s OK to devote time and resources to something important. And it feels great to accomplish so much and to connect with sources under new frameworks.

We designed the project’s website so that all the stories would flow on one page, so that readers could read and listen to all the content that had been published up to the day they visited the site. Because of that, the project’s metrics are a bit lower than we would have anticipated.

The project’s site accounted for 2 percent of all traffic over a six-week period, during which the stories were posted online and published in print. And readers spent an average of nearly four minutes on the site. Half of the online readers who read the project came directly to the website, with search on Google accounting for 28 percent and Facebook only 12 percent of traffic.

Revenue was a miss for us on this series. Both our news and advertising teams realize we need more defined options for advertisers to sponsor a series instead of strictly running their ads on adjoining content.

This is an approach we are continuing to refine at our property. KDUR, the main radio station that Sarah worked with to run the audio series, did see an increase in donations from listeners who cited the series as the reason they were donating.